Political Career of William A. Witman, Sr.

By CLEMENT J. CASSIDY

About one hundred years ago on October 19, 1860, to be exact William Abbott Witman was born in Reading. Although not destined for historical greatness, Witman was to become the best known politician of his generation in Berks County. In addition, Witman was to establish a reputation as a sports enthusiast and as a prominent builder and contractor. In this latter role he provided Reading with its most familiar and prominent landmark the Pagoda. But all this was far in the future in 1860, when William Abbott became first-born of six children in the Witman household.

Since William Abbott’s father, Hamilton W. Witman, was a master mechanic for the Reading Railroad Company, we assume that the Witman family had an economically comfortable life. William, after finishing high school, went to work in the Scott Works as a machinist. During the period encompassed by Witman’s start at the Scott Works and his debut on the political scene in 1886, he made two decisions which were to set the pace and method of his life he went into business for himself, and he decided to enter politics.

The first decision resulted in the formation of A. Witman and Brother, a coal yard enterprise which William shared with his brother, Jonathan (or John, as most people called him). This venture was soon superseded by a construction firm and, for a time, a quarry business on Mount Penn. Construction, however, turned out to be Witman’s chief life work. As a contractor, he has left Reading the most lasting evidence of its achievements. It would be difficult to list all the homes and structures he built during his lifetime.

As a result of the second decision mentioned above, Witman entered the city government in 1886 as one of the Common Councilmen from the Eighth Ward. Reading was governed, at that time, by a bicameral council as outlined in the Pennsylvania General Act of 1874 for the government of third class cities. There was a “lower house” or Common Council and an “upper house” or Select Council. Each council had its own president, and all legislative functions were vested in the councils. The actual legislative work was handled by joint standing committees

composed of members from each council. Separately elected officials (mayor, treasurer, auditors, etc.) carried out the executive functions. In most respects, the city government was modeled in miniature-on the national government in Washington. Although this cumbersome system had its origin in a Pennsylvania Act of 1847, it reached its fullest development in the Pennsylvania Act of May 23, 1889, which set a zenith for complication in local government. Of course, this dual council system finally gave way to the more efficient mayor-council system of today, the Clark Act accomplished this in 1913.

In his first year in city government, Witman served as a member of the Joint Standing Committee on Highways and Paving. Professionally interested and capable in this field, he was to serve in the following years many terms on this committee , indeed, his chief legislative Proposals, whether on the committee or not, centered around the upkeep of the streets of Reading. The citizens of northeastern Reading particularly owe William Abbott Witman a debt in this respect, for practically single-handed he pushed the legislation which spurred the development of that area. One of his earliest bills during his first term required contractors to employ only city labor in municipal contracts and fixed the compensation these laborers were to he paid.

Witman’s second election to Common Council indicated a vote approval from the citizens of the Eighth Ward, for he received 100 more votes than the year before. However, he received no committee appointment for this term and consequently was relatively inactive. An interesting bill he introduced at that session was directed against the Reading Iron Works, then situated on North Eighth Street. The Iron company was contemplating the installation of a thirty ton hammer-three times the weight of the one then being used. Witman championed the group of North Eighth Street citizens who feared for the peace and quiet of their district by asking council to enjoin such an installation. The bill was defeated. Scarcely less interesting-and indicative of his interest in streets-Witman presented a bill to council on July 25, 1887, for the allocation of $75 to be used by the Highway and Paving Committee to put Spring Street, from Eighth Street to the railroad, in passable condition. When this amount was used up, his firm of Witman and Weigle would finish the job at no added cost to the city. Witman had introduced several bills previous to the one above mentioned in an effort to get the Spring Street paving job done. He was apparently driven to the above recourse by two forces: council’s stubborn refusal to vote funds for the job, and his equally stubborn insistence that the project be carried out. The bill was finally passed.

After completing his second term as Eighth Ward Common Councilman, Witman moved into the Thirteenth Ward. Here he was to experience his greatest political triumphs. The beautiful grey stone home he built at 1127 Marion Street still stands today, he lived the remainder of his life in this home and in the Thirteenth Ward, which he had chosen as his own. In 1892, Witman ran for the office of Select Councilman for the Thirteenth Ward. He fought hard in the campaign but, when the results were announced, he was the apparent loser by a slim margin. The election returns were unsatisfactory to Witman, however, and he began a long appeal which was eventually to lead him into the Berks County Courts. Finally, on November 12, 1894, a strange series of Select Council meetings occurred. The Council had convened in the morning, but lacking a quorum, had to adjourn until later. This process continued all day and into the night. At last, after six abortive attempts to get a quorum, the Council finally met at 1:40 am., November 13, 1894, with a sufficient number present to do business. This lucky seventh meeting was a moment of great triumph for Witman. The business before the council was a statement from Judge G. A. Endlich of the Court of Quarter Sessions announcing a decision of November 12, 1894, on the contested Select Councilman election of the Thirteenth Ward held February 16, 1892, William Abbott Witman had 308 legal votes, Charles H. Ramsey had 307 legal votes, Abraham Whitman had 3 legal votes. Therefore W. A. Witman was entitled to the office. The council immediately swore Witman in and struck the name of Charles H. Ramsey from the rolls of Select Council. Although it had taken him almost three years to prove his claim to the office, Witman was now firmly back in city government, where he was to remain for some time.

This advent into Select Council was to begin an era lasting from 1894 to 1907, during which Witman became thoroughly grounded in city politics and developed the flamboyant personality so well known to his generation. Inseparable from this personality were the two Witman symbols: a winsome smile and an ever-present white carnation in his coat lapel. In the Select Council, “Witty,” a nickname Witman acquired both as a play on his name and as a tribute to his mental processes, established a reputation as a fiery fighter and holder of important chairmanships.

One of the newspapers of the time, the Herald, attempted on several occasions to profile the Witman personality. Since the Herald was never friendly to the Thirteenth Ward politico and later became his arch-enemy, its favorable comments on him should be considered fairly valid. In 1906, the Herald recognized Witman’s ” . . . readiness of wit, cheerfulness of disposition, that power of loquacity to which we have aforetime referred, that seem to mark Mr. Witman as a superior man and as therefore a proper person for leadership.” Again in 1908, the Herald called Witman, ” . . the most captivating of the five candidates for mayor . . Whether Mr. Witman be nominated tomorrow or not, he has performed a dashing campaign . . there is something about that carnation, about that smile, about those auburn locks, about his winsomeness and geniality that compels people to be his friend.”

But we must return to the beginning of the era and the Select Council of 1894-1895. After his stormy arrival, Witman was made Chairman of the Joint Committee on Highways and Paving, a position in which he took relish. In the next year’s session, he served on the Joint Committee on Police and the joint Committee on Tax. It is interesting to note that this latter session of council, recognizing the unwieldiness of its own system, called for a convention (to be held in Reading) of delegates from all third class cities in Pennsylvania to draft a new municipal act for third class city government and submit it to the 1896 Assembly in Harrisburg. Also during this 1895 session, Witman proposed a resolution which would set up a committee of three from the two councils to confer with the Reading Railroad on the advisability of erecting a bridge over the railroad’s tracks at Spring Street. This was the precursor of Witman’s famous Subway Bill.

In 1896, Witman was reelected to the Select Council from the Thirteenth Ward by the narrow plurality of four votes (487 to 483). He was once again made chairman of the Joint Committee on Highways and Paving and a member of two other joint committees, Sewers and Tax. The four years of his second term were directed toward developing northeastern Reading. It would be beyond the range of this study to list the innumerable bills he presented to pave streets, install street lights, and complete sewage hookups. One bill presented by Witman in 1896 had to do with a roadway that the Park Commissioners were planning to build across his rented property on Mount Penn, where the quarry he owned was located. According to Witman the proposed roadway crossed the inclined railroad to the quarry and would stop its operation. He requested that the city settle amicably the damages accrued from his closing down the quarry because of the uncertainty of the situation. Witman eventually took his case to Court. The Court of Common Pleas of Berks County ruled against Witman, who then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court but to no avail.

beyond the range of this study to list the innumerable bills he presented to pave streets, install street lights, and complete sewage hookups. One bill presented by Witman in 1896 had to do with a roadway that the Park Commissioners were planning to build across his rented property on Mount Penn, where the quarry he owned was located. According to Witman the proposed roadway crossed the inclined railroad to the quarry and would stop its operation. He requested that the city settle amicably the damages accrued from his closing down the quarry because of the uncertainty of the situation. Witman eventually took his case to Court. The Court of Common Pleas of Berks County ruled against Witman, who then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court but to no avail.

During the 1897-98 session, Witman served on the Joint Committee of Sewers. In the 1898-1899 session, he returned to his old position as chairman of the Joint Committee on Highways and Paving besides receiving a new assignment to the Garbage Committee. The last year of his second term (1899-1900) Witman was a member of two joint committees, Garbage and Sewers. At this juncture, Witman appeared well established in the Reading political world: he had won the battle in a disputed election, he had succeeded in being reelected, he had served on most of the important city government committees. On the surface it would seem that he was ready for bigger things.

The bigger thing on Witman’s mind was the mayoralty of Reading, for which he contested in 1908, 1911, 1919, and 1923. In all these elections he was able to produce a large turnout at the polls but, though some of the campaigns were close, he never could get the majority necessary to put him into office. Always his greatest political strength in mayoralty elections came from the Thirteenth Ward, which usually gave him an almost unanimous vote, and the northeast section of the city in general. (Apparently, the Thirteenth-Warders were undivided in their support of Witman for mayor, but, as will be shown, they tended to be fickle in their choice of Select Councilmen.) But the voting power at that time was concentrated in the southern sector of Reading, and Witman could make little headway there. In his mayoralty attempt of 1899, Witman didn’t get past the primaries. The year 1900 was also unfortunate for him, he lost his seat in Select Council to Edwin Mersinger by a vote of 631-590. For a short while “Witty” was in political decline.

Returning to the political wars with a vengeance, Witman was elected Select Councilman from the Thirteenth Ward for his third, and last, term in 1904 by a plurality of well over 100 votes. Once again he became Chairman of the Joint Committee of Highways and Paving and a member of the Joint Committee on Garbage. From 1905 to 1907, Witman was Chairman of the important Joint Committee on City Property. These were the most fruitful years of his life, the number and diversity of his activities were enormous.

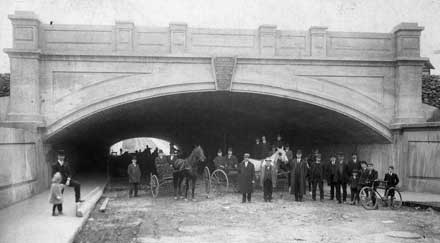

On July 10, 1905, Witman introduced the “Subway” Bill in Select Council. This bill called for the construction of an underpass on Spring Street, between Sixth and Eighth Streets. For years the Spring Street roadway had crossed the Reading Railroad tracks, many accidents had occurred at this hazardous crossroad, and agitation for removal of the danger had been mounting for a long time. Although the city government approved the plan, the subway still had not been built by 1907, and Witman used it as a platform plank in his second mayoralty campaign. Because of his strong interest in the underpass, he gained the nickname, “Father of the Subway.” It was largely through his efforts that the subway did not die aborning and is part of the present landscape of Reading.

During his last term in Select Council, Witman was involved in the incident which was to plague him to the end of his political career. There had sprung up at the turn of the century a non-partisan group of citizens, called the Taxpayers’ League, bent on eliminating corruption from government. This organization was a part of a larger reform movement afoot throughout the nation  at the time. Fired by the muck-raker’s spirit, the League had forced three corrupt councilmen to resign before they singled out Witman. In January, 1906, the league struck at Witman, accusing him of defrauding the city in a sand and spall contract as well as in a garbage collection contract. Witman commented at the time: “This is not a prosecution but a series of persecutions to drive me out of councils. I had no connection whatever with the weighing of spalls and garbage.”

at the time. Fired by the muck-raker’s spirit, the League had forced three corrupt councilmen to resign before they singled out Witman. In January, 1906, the league struck at Witman, accusing him of defrauding the city in a sand and spall contract as well as in a garbage collection contract. Witman commented at the time: “This is not a prosecution but a series of persecutions to drive me out of councils. I had no connection whatever with the weighing of spalls and garbage.”

Protesting his innocence, Witman was brought to court, where very damaging testimony was presented against him. Under a municipal ordinance then extant, a councilman could not be a party to a contract with the city. At the time, Witman and his brother were operating a quarry. Apparently, Witman sold sand and spalls to his brother, who in turn sold them to the city. As he explained in court, Witman and his brother owned the land surrounding the quarry jointly, but he owned the quarry. Therefore, John Witman was acting as an independent sand and spall hauling agent in his dealings with the city.

In the other charge, it was revealed that the garl)age weight reports, upon which city payments were based, were padded. How this involved Witman was a little cloudy, but the contract was negotiated by the Garbage Committee of which he was a member.

Finally, in 1906, Witman was found guilty of the charges by Judge Endlich in a quo warranto proceeding of the Berks County Court. Seeking to reverse the decision, Witman appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. His luck was no better than the last time he appeared before this august body. and the lower court’s decision was upheld. Naturally this decision created a great deal of unfavorable publicity for Witman. On April 15, 1907, he was ousted from his seat in the Select Council by court injunction. That same month he ceased his attempts at further litigation, paid the costs, and dropped the case. The stigma from the whole affair was by then inerasable.

Bounding back with gall and vigor, Witman announced his candidacy for the office of mayor on the Democratic ticket in the closing months of 1907. The Herald had not yet lowered its guns on Witman, as it was to do in later campaigns. Political campaigning was still a popular activity in those days, each ward had a hotel in which the ward leaders and followers met to listen to the various candidates present their platforms. Witman made many appearances in the different wards. From his speeches, an outline of his platform can be obtained. He contended that no one from the northeastern section of the city had ever been elected mayor, and that it was time for such an event to occur, for this was where the future expansion of Reading would take place (he was correct in his prophecy). He contended that the subway on Spring Street should be completed. The appropriations had been made, the contract awarded, he had started the project and, if elected, he would see it completed. He proposed that the whole police force be revamped: the police should be made to turn in their badges and requalify according to ability, the police should not be forced into political fund-raising activities in order to elect a candidate and thereby keep their jobs. If elected, Witman promised to create a Bureau of Complaints which would be open to all citizens. He cited his record as a champion of the fire companies’ needs. He also promised a chaplain for City Hall, mounted police in the rural areas, and a bridge across the Schuylkill River at the foot of South Sixth Street. The Witman slogan became “a dollar’s worth of services or improvements for every dollar paid in taxes.” This slogan was to be repeated continually in the many campaigns for mayor which Witman was to conduct. But all his campaigning came to nought, for he lost the primary election. Incidentally the Republican candidate won in November by an 1884 vote plurality.

Between the 1907 campaign and his third attempt at mayor in 1911 Witman did some of his most impressive building. In 1908 he completed the Pagoda. He had used the stone from his quarry for the construction, and he intended to operate the oriental structure as a hotel and tourists’ attraction. The pagoda was supposed to be a replica of the palace used by the Japanese Emperor Shogun while he was in exile in 1450, but the details were actually copied from a Japanese tea garden at Coney Island, New York. Witman spent $33,000 to build the Pagoda. Unable to operate it profitably, he soon sold out to Jonathan Mould, a Reading banker. Mould, in turn, donated the building to the City of Reading.

Also during his campaign interim Witman built the Circus Maximus at Thirteenth and Exeter Streets. He bought the ground upon which he erected the stadium on June 1, 1909, and soon thereafter Witman completed his house of sports and began promoting various athletic contests mostly baseball within it. The Circus Maximus was Witman’s climactic contribution to the promotion of sports, to which he devoted much of his time, effort, and money. He organized several baseball leagues, including the earliest in Pennsylvania history. But he was unable to make the Circus pay off. On August 15, 1912, Witman went into bankruptcy with his stadium, and it was sold to the Farmers’ National Bank of Reading for $38,000. Both the Pagoda and the Circus Maximus (today the Albright College Stadium) will symbolize for many years the building prowess and promotional abilities of William Abbott Witman, Sr.

Witman again appeared on the political stage in 1911 when he sought the Democratic nomination for mayor for the third time. This election was a real heartbreaker for Witman. He conducted his usual vigorous campaign, and, when the unofficial results of the primary balloting were announced, he had a slim edge of 29 votes. For all practical purposes, he was the Democratic candidate for mayor in the November election. A few days later, however, an official recount revealed that Edward J. Morris, Witman’s primary opponent, had a 23 vote plurality. With characteristic aplomb, Witman commented, “Notwithstanding my temporary nomination on the Democratic ticket for the highest office in the gift of the people of this city, it is my intention to stand by the decision of the umpire and support the Democratic ticket.”

The year 1915 was the last Witman victory. As has already been mentioned, the city government was modified in 1913 by the Clark Act, and was now headed by a mayor and four councilmen. Witman sought election as a councilman on a non-partisan ticket (before the Clark Act was modified, party labels were forbidden by law in municipal elections). The Herald leveled a scathing attack on him, reminiscent of that of the 1913 campaign when he had lost the first election for councilman under the new system. In the latter campaign, Witman had retaliated with a $50,000 libel suit against William McCormick, proprietor and editor of the Herald, and several other men. This suit had been dropped when the Herald paid the costs. In 1915, Witman ignored the Herald with rewarding effect. Perhaps the citizens of Reading remembered this time what he had said in 1913: “There are three keys to governmental success: discretion, fidelity, and steadfastness. With the new form of government, we must not cast out those who have served faithfully and well in the past.” This time Witman was elected councilman of the City of Reading by 7210 votes. As Superintendent of Public Safety, he served his last two years in public office (1916 and 1917).

The most spectacular event of his last term in council was a fist fight which occurred on March 7, 1916, between Witman and his fellow Councilman B. Frank Ruth. The fight broke out in the City Clerk’s Office in City Hall, it was a culmination of a long, deep-seated enmity between the two men, an enmity heightened by a statement Ruth made about the clean sweep of the Democrats in all city offices in 1915. At that time he termed Witman the “fly in the ointment.” The fisticuffs in City Hall received far greater publicity than any of the subsequent legislation Witman was to introduce to council.

The old Thirteenth Ward Select Councilman, bringing his twelve years of experience in city government to bear, served well in his last two years. Although still interested in paving, resurfacing, and street repairing, Witman began to wage a private war on all privy vaults (outside toilets) during the 1916 session. His war culminated in a bill he introduced on September 20, 1916, which banned all privies within reasonable distance of city sewers, and required that all cesspools, walls, pits, or excavations used for deposits of human or animal excreta be filled in. In the latter part of 1916, Witman presented a bill which created the office of City Health Officer.

Witman spent the year 1917 mechanizing the fire companies and modernizing all fire and police alarms. Incidentally, William McCormick, Witman’s antagonist mentioned earlier, was brought under council fire in 1907. In his Herald he had accused the police of Reading of receiving graft, but refused to release evidence of the charge to council so that it could act.

Almost as though Witman had a premonition that he was at the end of his political career, he had a perfect record of attendance in the 1917 session. The political growth of William Abbott Witman was complete, the years to follow were marked by anticlimaxes, decline and defeat.

In 1919, Witman made his strongest race for mayor. In this campaign, his fourth attempt, he was the only Democratic nominee and thus, for once, weathered the primary. But the opposition was too strong, and the returns of the November general election told the story: Stauffer (Rep.) 7421 votes, Stump (Soc.) 5649 votes, Witman (Dem.) 3837 votes. It was all over. Witman ran for office after that, but his political potency was finished. In 1923, he lost in an election for delegates to the Democratic National Convention. In 1925, he attempted to get an appointment as consul to Brazil, but was unsuccessful. In 1927 and again in 1933, the old political war horse fought for Councilman, but never got beyond the primaries.

Three years after his last campaign, on February 12, 1936, William Abbott Witman, Sr., died at St. Joseph’s Hospital. The newspapers gave little space to the passing of this grand old politician and citizen of Reading. It could very well be that this was because his human frailties were too often put before the public, perhaps he tried too hard in his political campaign. No one could objectively say that Witman was overly scrupulous in his political dealings, but then it must be remembered that he lived in an era when political unscrupulousness was the rule rather than the exception. The Herald put it in succinct terms in 1908: “Mr. Witman’s record is a strange mixture of the bad and the good.” To put it in “Witty’s” own words, an acquaintance of his (one who grew up in the Thirteenth Ward when Witman was at the height of his power) quoted him as saying, in reference to city politicians: “They’re all liars and crooks, I’m not a liar.”

When Witman died, a chapter in Berks County history closed. It was a local and old-time-era chapter, but important, nevertheless.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 1958 issue of the Historical Review of Berks County.