Mineral Spring Park, Pendora Park,

The Zoo of the City of Reading, and Removal of Animals to Memorial Park, Williamsport, Pennsylvania

By EDWIN L. BELL, Professor Emeritus, Albright College

Editor’s Note: Dr. Edwin L. Bell, a resident of Reading, is a graduate of Bucknell University, the Pennsylvania State University and the University of Illinois (where he received his Ph.D. in biology).

Mineral Spring Road leads eastward from Reading and passes over the Lindbergh Viaduct into the town of Mt. Penn. The name of this road came from the nearly forgotten Mineral Spring Park, located just north of the Viaduct in Rose Valley. In 1815 two Reading businessmen, Charles Kessler and John Spade erected a stone textile mill, powered by water, at the lower end of the glen. The factory failed in 1818, allegedly because the business could not compete with foreign goods. A spring was discovered upon the property, and the building was eventually named the Mineral Spring Hotel. In 1818 the mineral water from a spring was promoted: “The analysis of these waters will show it does contain some of the same mineral ingredients as those of Schooly’s mountain in Jersey, and other mineral waters. Experience has already shown their efficacy in strengthening weak nerves, [guards] against water in the chest, against gravel [kidney stones], and as a tonic in general. Persons being afflicted with sore eyes have been relieved by the application of these waters.

“The subscriber therefore invites all those who wish to make use of these waters to call at his tavern and he shall make it his duty to entertain them so well and agreeable, and at such moderate prices as shall be in his power”.

“His endeavors shall likewise be directed to entertain with the best liquors and victuals all those who may wish to visit this place merely for their amusement. Therefore he generally solicits the custom of a generous public. Jacob Schneider, proprietor.”

Dr. Isaac Hiester, one of Reading’s most notable physicians of that era reported that the water contained iron, held in solution with carbonic acid gas, together with a small quantity of soda. At that time fresh air, herbal medicines, and mineral waters were recommended for a variety of ailments.

From 1827 to 1837 Mrs. Catherine Kessler and her two daughters managed the hotel, and generally enjoyed a profit of $1600 a season, which was quite a sum in those times.

Mineral Spring H6tel was converted into a “fashionable hotel” in 1837, and ran until 1856, when the Reading Water Company purchased the property. The East End Athletic Club is the surviving remnant of the Hotel, and is still in operation. During the nineteenth century James Buchanan, George Dallas (James Polk’s vice president), and probably Rutherford B. Hayes were some of the guests of the Hotel.’ Buchanan, who was then a Senator from Pennsylvania, addressed a gathering of 1500 persons there on July 4, 1840. Three militia bands accompanied Buchanan, Congressman George May Keim from Berks County, and Vice-president Richard Johnson (under President Martin Van Buren) to a podium in the Park. Hayes visited Reading on October 26, 1875. His host, General Lemuel Todd of Carlisle, is reputed to have remarked that the rum punch served at Mineral Springs Hotel was beyond price or praise.

During the nineteenth century the Democrats of Reading held annual Fourth of July celebrations in the park.’

A spring, with an estimated daily minimum flow of 120,000 gallons, was once one of the main sources of Reading water. However, the city has not used the area as a water source since about 1880. The mineral spring no longer flows, and has been abandoned. Montgomery (1886) describes the water source: “The mineral spring was walled at that time, and an octagonal building erected atop eight iron pillars with open sides and a roof.”’ No such structure exists today.

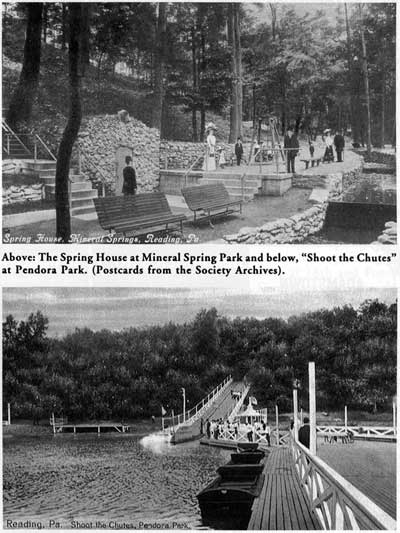

A commercial amusement park, Pendora Park, was opened on July 25, 1907, with a reported 20,000 persons attending.’ Admission to Pendora Park was five cents, whereas there was no admission fee to Mineral Springs Park. William P. Sweny was the owner-manager of Pendora Park, which had a 2,250 ft. midway, and a miniature railroad.

The former Sweny’s ice dam became a large lagoon. The midway had a roller skating rink, a bowling alley, a shoot the chutes (a water slide upon which a boat could shoot downward into the lagoon) a penny arcade, ice cream parlors, and a merry-go-round. On Jan. 3, 1911, the park burned, and only a band shell and the merry-go-round were saved. Pendora Park never opened again as a commercial venture. In 1917 a severe thunderstorm caused a flood down Rose Valley, which burst the ice dam, causing a wall of water to rush down 18th St. and Perkiomen Avenue. Under pressure from William L. Moser, president of the Sixteenth Ward Improvement Association, the City of Reading bought the land in 1918 and converted it into a city playground, which still is called Pendora Park.6 The ice dam was filled in and presently is a baseball diamond.

The dam embankments are still visible around the present baseball field in Pendora Park, and little imagination is required to see it as a former spacious lagoon filled with water. Rose Valley Creek is confined by a stone bed and walls laid by stone masons in Mineral Spring Park, which eventually empties into a storm sewer at 18th and Forest streets. Stone archways cross the creek, and several stone-enclosed springs still are visible. Presently several pavilions are being restored by the City of Reading. This sixty-three acre recreational area was a popular picturesque place in the early nineteen twenties, being visited by many Sunday school outings. One of the main junctions of the Mount Penn Gravity Railroad was in Mineral Spring Park. A slab of concrete at the east end of the Lindbergh Viaduct is the only remnant of a car barn, the Gravity Station, for the Gravity Railroad. The slab overlooks the present tennis courts of Pendora Park.7 The old railroad grade can plainly be seen on the east side of Mineral Spring Park. The railroad proceeded northward through the glen, and passed just east of the dam in Egelman ‘s Park. A photo of an open railroad car at Egelman’s dam is in the Passing Parade, Vol. 1, No. 1, p. 247, (Meiser and Meiser, 1982).

Henry Wharton Shoemaker (1882-1958) was a banker, diplomat (to Portugal, 1904; Berlin, Germany, 1904-1905; and Sofia, Bulgaria, 1930), and newspaper publisher. He had a philosophy of conservation far ahead of his time. He served in the Pennsylvania National Guard from 1905 to his death, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. As a youth he spent many summers at his maternal grandparents’ home, Restless Oaks, in McElhatten, Clinton County, Pennsylvania. He became fascinated by the folktales he heard from the settlers in central Pennsylvania, and was greatly interested in the animals of the area. He was the author of twelve books of folktales, and wrote many articles on various animals, which were published in the Altoona Times-Tribune, or as short pamphlets. He was the successive owner and publisher of newspapers in Jersey Shore, Bradford, Reading, and Altoona. From 1912 through 1950 he was the owner and publisher of the Altoona Times-Tribune. In 1908 he purchased the Reading Times and Dispatch, and changed the name to the Reading Times. The last time his name appears as President of the Reading Times was late June, 1912.

He strongly advocated the elimination of the bounty for large predators such as the mountain lion, bobcat, and wolf. He was particularly enamored by the mountain lion. He stated that one must promote the survival of these large mammals which perform a valuable service by preying on rodents, by removing aged and sickly prey, and by keeping the deer herd in check. He clearly stated that bounties were a waste of the state’s money.”

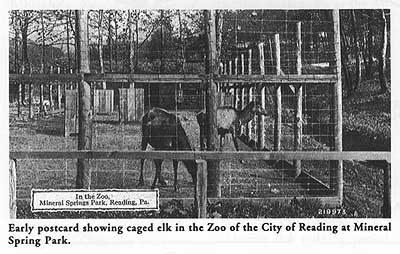

In 1913, while Pendora Park was in operation, and before the dam for the lagoon was ruptured in 1917, Colonel Shoemaker donated a number of animals to the City of Reading, to be the nucleus of the Zoo of the City of Reading. The offer was made in 1911, to the then Mayor William Rick, but the donor’s name was not revealed until later. Col. Shoemaker was a frequent visitor to Mount Penn (the mountain), and is said to have greatly enjoyed the social life of Reading. The zoo was comprised of at least two elk, two fallow deer, two black bears, two Canada geese, two horned owls, a silver pheasant, and a number of squirrels. Pens housed the animals in either Mineral Spring Park or the adjacent area of the defunct Pendora Park. Several swans were donated by William H. Luden, and could be seen on the lagoon. The zookeeper was John Jacob Roth (personal communication from his grandson, Norman F. Butt).

Due to complaints that the cost of feeding them was too great, and from the Humane Society that the animals were not being properly cared for,  the City of Reading arranged to transport the animals to the Williamsport Memorial Park, for a zoo there. On 29 May, 1924 a number of men supervised the crating and removal by truck of the animals. Those responsible were George R. Flemming, Superintendent of the Williamsport Department of Parks and Public Property; Reading councilman Edward C. Hunter, Reading Park Superintendent; William I. Hoch, Park Engineer; Charles F. Fenstermacher, state game protector; C. E. Logue, of Woolrich, trapping instructor for the Game Commission; J. J. Slautterbach of Harrisburg, chief of the Game Commission’s bounty division; and Frank Keller, superintendent of the Williams-port Memorial Park.

the City of Reading arranged to transport the animals to the Williamsport Memorial Park, for a zoo there. On 29 May, 1924 a number of men supervised the crating and removal by truck of the animals. Those responsible were George R. Flemming, Superintendent of the Williamsport Department of Parks and Public Property; Reading councilman Edward C. Hunter, Reading Park Superintendent; William I. Hoch, Park Engineer; Charles F. Fenstermacher, state game protector; C. E. Logue, of Woolrich, trapping instructor for the Game Commission; J. J. Slautterbach of Harrisburg, chief of the Game Commission’s bounty division; and Frank Keller, superintendent of the Williams-port Memorial Park.

The transfer of the animals met with the approval of Col. Shoemaker. The swans were returned to William H. Luden, and the ducks were returned to Mr. Roth. However, the crating and removal of the animals was both frustrating and amusing, as the animals protested by making various kicks, grunts, and growls. They made front page news in the Reading Tribune.Io Crates were made for all the large animals. The fallow deer refused to enter their crates, and had to be rounded up and carried kicking to their crates. “Rose,” the female bear entered her crate willingly, but her mate “Teddy” fought the workmen for two hours. He ignored the bribery of food placed in the crate. A hose was turned on him to attempt to get him to enter, but he shook himself and sprayed water over his would-be captors. Two attempts to use blazing torches to scare him into the crate were futile, since he slapped them out with his paws. Finally he was captured and crated.

“Buck” and “Kitty,” the bull and cow elks, caused some excitement. They were not easily captured, but no one was injured by their hoofs and horns. Hoping to entice her into the crate, Jacob Roth placed a wheelbarrow load of freshly cut grass in her crate. “Kitty” went to the rear end of the crate and got a meal of the grass by pulling it out through the openings of the bars. “Buck” was the last animal to be crated. The truck crossed the Penn Street bridge at 4:00 P.M., and the animals were taken to their new homes.”

Williamsport City Council had approved an appropriation on May 9, 1924, made by George Fleming, of not more than $3,000 to construct pens and proper enclosures for the animals. Fences for the elk and deer were estimated at $345 each, and a bear pit was estimated to cost $350. The animal shipments were from Reading and McElhatten, with the latter city [or perhaps Col. Shoemaker] contributing one timber wolf, one wildcat, and two coyotes. Col. Shoemaker is reported to have donated an eagle.

The Memorial Park Zoo was a delight to both children and adults. The zoo complex was situated parallel to Beeber St. just north of the West Fourth St. entrance to the park. The complex was most popular in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and contained a Canada Lynx donated by J. August Beck, a male mountain lion, anteaters, a bison, a raven, wolves, jackals, barn owls, opossums, roosters, alligators, turtles, and waterfowl. A children’s contest to name a newly born bison was quite popular. Names submitted were “Nickel,” “Nickey,” “Bill Nick” (meaning “Billtown Nickels”), “Scott, “Uno,” “Tiney,” and “Billy.” Reading can be proud of its contribution to this zoo.

The Depression took its toll on the once-popular zoo. As the animals died off, they were not replaced and in the spring of 1933 only a few cages remained.

The author is grateful to Mr. George M. Meiser IX for providing advice and photographs for this article; to Barbara Gill, Librarian of the Historical Society of Berks County; and to Robina Rader, Reference Librarian of the James V. Brown Library of Williamsport for providing information on the Memorial Park Zoo.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 1995 issue of The Historical Review of Berks County.