| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 5 |

Fairs Held In Penn’s Common (City Park Annals Part IV)

From “The Passing Scene Volume 4”, Meiser and Meiser

Few, other than the most ardent local-history buffs, are aware that between 1854 and 1887 the Reading Fair – more correctly, the fair of the Berks County Agricultural and Horticultural Society – was held annually in Penn’s Common on grounds reserved solely for that purpose.

On May 13,1854 the county commissioners of Berks leased about 39 acres of prime park-land to the aforementioned society for a term of 99 years, for the nominal consideration of $1 per annum.

Forthwith, the land was enclosed with a sturdy 8-foot-high wooden fence and the public accordingly became debarred from its use except by permission of the agricultural society.

FOR THE RECORD, the Berks County Agricultural and Horticultural Society dates from Jan. 13,1852. Its first exhibition took place on Aug. 17,1852 in the parlors of Daniel Housum’s “new hotel,” located on the southwest corner of Fourth and Penn streets.

This hotel survives as the American House, restored in superlative fashion by Peter Carlino of Wyomissing.

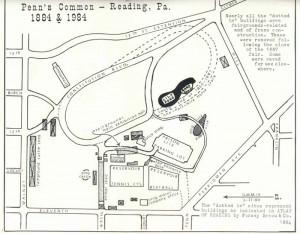

THE FIRST FAIR held in Penn’s Common occurred in October 1854. Among the initial improvements made to the grounds were the erection of a commodious exhibition hall and the laying out of an oval racetrack, one-third mile around.

Over the years buildings were added, some were enlarged, and older ones were moved or removed. No two maps of the grounds are identical or even nearly identical, so numerous were the ongoing changes.

Historian M. L. Montgomery reports that a Civil War military hospital was “fitted up” in the middle of June 1862 in the main exhibition building on the fairground with cots sufficient to accommodate 130 patients. This emergency arrangement continued until the spring of 1863. Accordingly, during these two years, and 1864 as well, no fairs were conducted.

IN 1865, PRIOR to resumption of the fair, the racetrack was increased in length to a half mile, and the grounds were

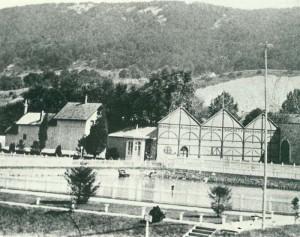

The fairground in Penn’s Common was entered by walking up a roadway that extended eastward from Penn Street and then turned left and continued along between reservoir and the prison’s west wall. Notice that the entrance to the grounds, where visitors walked through one of two turnstiles and paid their 25-cent admission fee, had a massive front – not unlike a movie-set structure. In the foreground is the open South Reservoir which, though now covered, remains in use

extended northward one block to Walnut Street and enclosed with the same type of fencing found elsewhere around the fairgrounds.

As the racetrack’s oval configuration extended north and south and the park itself slopes steadily in an east-west direction, particularly on the southern end, it became necessary – for the sake of levelness – to build up that southern end rather considerably.

Be apprised the steep bank running behind the band shell is the remains of this 1865 effort to construct a racetrack with a “nearly flat trotting area.”

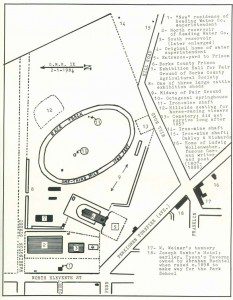

The above rendering, showing the area in and around the developed portion of Penn’s Common, is based on Geil & Shrope’s wall map of Reading, published in 1857.The land north of Washington Street, actually a part of “the Commons,” was under the control of the county commissioners at the time. From 1854 to 1887, the Berks County Agricultural Society had exclusive use of 39 acres of prime parkland as a site for its annual fair.

In 1878 a movement was made to improve that part of the commons that lay between 11th and Penn and the present-day intersection of Hill Road and Clymer Street. Concerned citizens donated over $6,000 toward the project, which was pursued with vigor.

ACCORDINGLY, IT became necessary to move all fair-related structures in that triangle to the northern end of the grounds. Close examination of an accompanying photo reveals that the vacated area was literally clustered with buildings and pavilions.

This forced move was not the last one in store for the agricultural society.

Without disclosing the full details of the matter, which will be presented in the final segment of this five- part history of Penn’s Common, a Supreme Court decision in 1885 transferred control of the common from the county commissioners to the city of Reading. Consequently, the fairgrounds had to go.

City officials, realizing that it would take some time to acquire a new site and ready it for the public, allowed the agricultural society to hold its exhibitions in the park until October 1887, at which time all remaining fair-related structures – including fencing – would be removed.

IN 1936 Miriam L. Stirl, a local educator for some years, prepared a modest monograph on the history of the Reading Fair. In pursuit of human interest material, she prevailed upon the collective memories of A. H. Kretz, Arthur Wittich, and Charles W. Swoyer.

What follows are bits and pieces from her compilation, which serve to give some idea of the nature of the old-time fairs in Penn’s Common.

“Massed visitors jammed up the drive to enter first the Horticultural Hall (main building), a long, frame, slate-roofed structure with offices in the eastern end. In the rear a ‘restaurant’ was located, its abundant water supply coming from the arched spring near the gravel hole (near the present greenhouse).

“Massed visitors jammed up the drive to enter first the Horticultural Hall (main building), a long, frame, slate-roofed structure with offices in the eastern end. In the rear a ‘restaurant’ was located, its abundant water supply coming from the arched spring near the gravel hole (near the present greenhouse).

“One year in the northern end of the Hall a handsome fountain was installed, which splashed to the sweet accords of a Bohler organ. Here, passing thousands saw tables piled with orchard and garden fruits, and, cynosure of greatest interest, pumpkins.

“LATER, AN adjacent Machinery Hall housed the farm implements which were to more and more affect farming. One year the machines were run by water-wheel-power operated in the pipes carrying water from Egelman’s Spring to the reservoirs in the Common.

“The whole county was alive during Fair Week, and the city of Reading fairly teemed. Indeed, teams were double-parked along the streets and the stables were packed as the people poured up Penn Street.

“Residents on Penn Street above Tenth built temporary platforms where they sat with family and friends all day watching the big parade walking to the fair.

“Wooden steps were made to the race track, which was improved one year, after washing rains, by the horsemen who later lamented that the bicyclers preempted the track and prevented the horses from training.

This rare view of the Penn’s Common fairground, taken in the mid-1870’s, looks northwestward from about the present-day intersection of Hill Road and Clymer Street. Notice to what extent the racetrack stands above the fairground buildings to the left. Notice, too, the 159-foot-long grandstand along the western length of the track.

“A. H. KRETZ, starting judge of races 50 years, pointed out where the speed matches ran over the oval, then a clay track extending up around the present lily pond and turning northward along the hillside. Here the spectators climbed wooden stairs to wooden benches on the hillside, high above the track.

“Milk at two cents a glass and pear cider were thirst quenchers. The W.C.T.U. served coffee and in 1887 came the first mention of Hot Frankfort Sandwiches. The huge Western Milling concern gave free handouts of griddle cakes with syrup, and buttered muffins.

“Whistle men (who sold whistles), Punch and Judy shows, wandering and tented photographers, shooting galleries, and ring-toss stands lined the dusty avenues of pleasure.

“A miniature working Atlantic Cable, balloon ascensions (as early as 1857), and band concerts from a special pavilion in the centre of the racetrack by the famous Ringgold Band, ‘the best to be procured,’ were great attractions and long remembered.”

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 5 |