| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 4 | Part 5 |

Berks County Prison In Penn’s Common (City Park Annals – Part III)

From “The Passing Scene Volume 4”, Meiser and Meiser

In 1794 the Pennsylvania Legislature – taking the worldwide lead – abolished death as a penalty for all crimes except that of premeditated murder.

In so doing, it became imperative to give second thoughts to the way prisoners were to be detained for lengthy periods of time.

The 1770 Berks County Prison – erected at the northeast corner of Fifth and Washington streets, on the site of the Berkshire Hotel – was typical of the “countie gaols” of the colonial period.

IN THAT ERA, little effort was made to classify detainees. A hapless and easily intimidated debtor might find himself thrown in with convicted felons and suspected cut-throats. Equally bad, women offenders were not entirely separated from their male counter-parts. Attorney Louis R. Richards once observed, “As jails were regarded as houses of detention merely, rather than reformatory institutions, discipline was necessarily lax, and the utmost vigilance of even a well-disposed Sheriff could not prevent many of the evils which gave to them the character of nurseries of vice rather than schools of virtue.”

Obviously, something had to be done.

Under the leadership of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, our Commonwealth adopted the principle of separate and solitary confinement of all convicts.

Advocates of the separate-and-solitary system were convinced that the way to teach an offender to live honestly and honorably as a member of free society was to require him or her to spend the term in prison in complete solitude, deprived of all human contact.

THE ENFORCED solitude would, they reasoned, compel the prisoner to meditate and study the scriptures – and thus reform. Relative to this notion, the late Paul N. Schaeffer observed that “It was like trying to teach a boy to swim by keeping him out of the water.”

In any event, Berks needed a new facility in order to implement “the Philadelphia plan,” and as the existing prison site was adjudged “woefully lacking,” another location had to be chosen.

As it was deemed advantageous to keep the prison “in town,” at the county seat and near the Court House, and as the county commissioners had at their disposal Penn’s Common, which was only blocks away and right along a main thoroughfare, the decision was made -with little hesitation – to erect “the new penitentiary” there.

IN 1847, commissioners John Sherman, Michael Gery, and Fred Printz engaged John Haviland of Philadelphia, the foremost architect of his day, to design an appropriate structure in keeping with the principle of separate-and-solitary confinement.

The late John Tenschert, pioneer Reading Eagle lens man, took this photograph on Jan. 21, 1932, the day the prisoners were moved to the new county prison on the W.W. Essick tract in Bern Township. This view clearly shows the details of “the great tower” and the two 50-foot-high octagonal bastions that stood on either side of the main entrance.

The new prison, completed in 1848 at a cost of $17,000, stood at the head of Penn Street on a lot that measured 170 feet across the front and 300 feet deep. This parcel, the exact boundaries of which remain intact, is now set apart for the exclusive use of police vehicles and personnel. The original retaining walls and front steps of the prison also survive here as convenient points of reference.

Constructed of sandstone extracted from Penn’s Mount, the new facility – often described as Gothic or Norman in styling – was dominated by a huge circular lookout, “the great tower,” which rose to a height of 96 feet. In front and to either side of it were two 50-foot-high octagonal bastions with elongated and barred interstices.

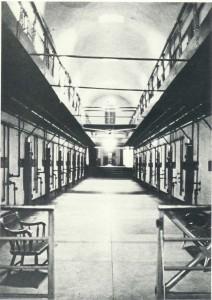

THE AFOREMENTIONED Paul N. Schaeffer, once president judge of the Berks County Courts, penned the following account in 1947, which gives a good idea of the nature of confinement in the early days – prior to the Civil War: “It was the intent of the law that prisoners should not, during the term of their sentence, be permitted to leave their cells. Food was handed to the inmate through a wicket in the latticed iron door.” (See accompanying photo.)

“The prisoner was permitted no visits and no letters or other communication with the outside world.”

“Proponents of the (Philadelphia) system realized that the preservation of the health of the inmate de- manded that he be given some chance to exercise in the open air. Therefore, there was constructed a separate exercise yard for each prisoner.

“EXERCISE YARDS for the ground-floor cells were immediately beyond the outer wall of the respective cells and were reached by crawling through a small aperture in the wall, about three feet high. These individual yards were 33 feet long and 8 feet wide, surrounded by high walls but open to the sky.”

Here is the original 1847-1848 cell block that extended northward from the base of the great (94-foot-high) tower. Within this corridor were 44 cells, eleven on each side and on each story. The five steps seen in the rear led to the 1889 annex, which was built to contain another 50 cells.

“The exercise yards for the second-tier cells were ten in number, arranged in (fan-like) segments of a semicircle located immediately to the north of the cell building, and were reached by a stairway. To get to these, the second-floor prisoners were led one at a time -with bags over their heads.”

The design of the prison embodied architect Haviland’s unique plan for heating and ventilating the cells. Relative to this, Schaeffer recorded the following:

“AT THE REAR (north) end of the building was a small tower which rose about 10 feet above the outer wall and was capped by a cowl, like a ship’s ventilator, which could be turned to receive the breezes.”

“Air was supposed to descend the tower to a basement corridor which was directly beneath the first floor corridor. In cold weather, the air in passing through the basement corridor was to be heated by a pipe, extending the length of the corridor, which was heated by hot water from a furnace in the rear of the prison.”

“From the basement corridor the air was carried by channels, constructed in the walls, to the top of each cell. The fresh air, after entering the cell, was supposed to escape through a vent in the base and opposite side of the cell into channels in the outer walls, which then led to the base of the great tower.”

“A fire was kept burning in the hope that the upsurge of heat from this fire would assist the circulation of air throughout the system.” From all accounts, this system was more impressive in theory than in reality.

IT IS PROBABLE that not too long after completion of the prison, officials experienced some difficulty adhering to the one-prisoner-to-a-cell concept. For example, in 1860, at a time when the facility had but 44 cells, a record 622 persons were confined. Granted, some of the stays were one-night events.

In 1869 it became necessary to construct an addition that provided another 50 cells. This rear cell house, also of two stories, extended east and west at right angles to the original structure. Construction of this annex did away with the rear exercise yards and the solitary confinement system generally.

By the late 1920s, the prison in Penn’s Common, which in 1847 had been acclaimed “the best in the country,” was inadequate for its intended purpose.

BEYOND THIS FACT, considerable structural decay was apparent, particularly around the front wing walls, and, indeed, there were those who felt it was high time to rid Reading’s premier park of its bastille.

Consequently, a new county prison was constructed in Bern Township. On Jan. 21,1932, all prisoners were moved to the new facility. Thereafter, the old building “sat empty” until its eventual and gradual razing. Numerous ideas were forwarded for possible uses of the old structure which many Readingites wanted preserved. Mayor Heber Ermentrout hoped it could become a recreation center. Others saw it as the ideal place for a new Reading Museum.

William E. Weidner, a Spanish-American War veteran and a spokesman for various military groups, wanted the facade retained as a war memorial or band concert “backdrop.” Officials liked Weidner’s suggestions but raising the necessary $200,000 was an impossible task during the depths of the Depression.

UNTIL A FINAL determination could be made as to its future, the city paid James P. Kane to watch and patrol the prison from dusk to dawn. Kane’s greatest concern was the rat problem, which was formidable.

After the prisoners and staff departed, scraps and crumbs of food were nonexistent and the rats became desperate. Hunger drove them to leave the place in packs and attack the fish in the lily pond.

By June 1934 parts of the prison had been torn away. There were still hopes, however, that something could be done with the outer walls, the great tower, and the twin bastions. Regrettably the situation proved hopeless and by 1936 nothing remained except that which can still be seen.

As might be expected, officials salvaged all they could. Much of the stone found its way into retaining walls and WPA structures. The field house at Baer Park, West Douglass and George streets, was built entirely from “prison stone,” in 1938.

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 4 | Part 5 |