| Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 |

Commons’ Sold By Penns For $440 (City Park Annals – Part I)

From “The Passing Scene Volume 4”, Meiser and Meiser

For more than a century after Reading had been laid out, the large tract at the head of Penn Street — about 85 acres originally — was referred to as the “Commons”.

While tradition had it that this parcel always “belonged to the town,” in view of the fact it had in 1749 been reserved by the proprietaries of Pennsylvania as a free and public commons, the tract actually remained the domain of Thomas and Richard Penn until sold through their attorney, Edmund Physic, to the county commissioners of Berks.

The transfer to commissioners Peter Feather Jr., Jacob Roads, and Jacob Epler occurred on Nov. 19, 1800, for the nominal fee of 440. While the deed for “lot 60” — available for inspection at the Recorder of Deeds office in Deed Book A, page 303 — contains no clause of restriction, it was taken for granted that the tract (incorrectly recorded as containing 55.5 acres) would remain public commons for the dwellers of the town.

The Penn’s implicit wishes notwithstanding, later commissioners came to regard the land as county property, to be used as they saw fit.

Prior to 1821 when the Reading Water Company commenced operating, the ordinary citizens of Reading were obliged to secure whatever water they required from the Schuylkill, wells, public springs, and cisterns.

Because of the heavy limestone content in the town’s well-water supply, which made the water generally ill-suited for washing purposes, women who lacked access to cistern-water arose early in the morning — often while still dark– to secure choice positions at some public spring.

The best of these was in what is now Penn’s Common — “City Park” to the unenlightened.

In regard to the foregoing, in 1885 historian M. L. Montgomery recorded the following: “Many people resorted to the Commons, along the stream that flowed from the ‘arched spring’ near the ‘gravel hole’, to carry on washing. The most popular potion was at the head of Washington Street, within several hundred feet from the present entrance into the ‘Fair Ground’.

“Many women and girls were there at a time”. The days most commonly devoted to this purpose were Mondays and Tuesdays. The numerous heads bobbing up and down over tubs, and long lines, and the ‘wash’ flapping in the breeze, presented an interesting sight indeed.

“The water was heated in large iron kettles, suspended from cross-bars which rested on notched upright posts, or placed on a temporary hearth built of stones gathered from the vicinity.”

RELATIVE TO WASHDAY, a 1906 Eagle article quoted “The late Mrs. Elizabeth Rapp” of 420 North Ninth who recalled the following from her girlhood — in the 1820s: “The women used to bleach the wash on the grass in the streets, excepting Penn and Fifth. I recollected well when there was a small reservoir at the head of Penn, and there was a low frame building over it, the door of which was locked. The water that was not needed to run through pipes down Penn was allowed to flow down South Eleventh, and my mother used to go to that street between Penn and Franklin to do her washing, on account of the water coming from the reservoir being soft, as that in the well was hard limestone water. The wash, tubs, and washboards were hauled to that place on a wheelbarrow from our home, corner of Orange and Franklin. After being washed, the linen clothing was laid on the grass in the street to bleach.”

BEYOND RESORTING to the Commons for drinking water and doing wash, the grounds were used for a variety of other purposes. Old writings note that some grazing of livestock took place here and, at times, “hay was cut by various parties.”

Public hangings were conducted at “gallows hill”, a prominent point in the Commons, located within the triangle bounded on two sides by Perkiomen Avenue and Hill Road. Those intent upon looking for the “hill” are advised that extensive grading in 1878 removed it.

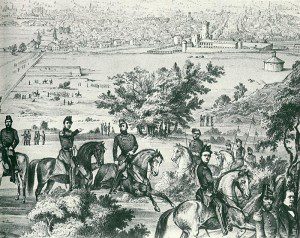

The old lithograph, “Battalion Day Scene in Reading”, shows the towns ranking military leaders posing in the upper reaches of Penn’s Common. Looking westward into the background we see the walled-in cemetery along Hill Road, middle left; Rambo’s Hotel, left rear; the Berks County Prison, middle rear; and the octagonal springhouse, which was a landmark in the park.

Incidentally, in this same triangle a small graveyard existed that some sources suggest might once have been used for Hessian burials. Later it served briefly as an interment site for paupers and criminals. The walled cemetery, which lay along hill road, can be seen in an accompanying illustration.

WHILE IT IS relatively common knowledge that there were a number of iron mines around the foot of Penn’s Mountain, on the south and west sides especially, it is not generally known there was a mineshaft right in the Commons, remains of which existed into the 1860s.

The exact location of this site can be determined by beginning at the stone, park-entrance pillar at the head of Penn Street — the one with the date 1893 cut into it — and measuring due east 1000 feet. At this point, turn to the left 50 feet due north, and you’re there.

BETWEEN 1798 and the end of the Civil War, Battalion Days and the militia system did much to keep alive the martial spirit of Berks. Annually, the various battalions came together — not infrequently for a whole week , particularly during the early period. Often the chosen gathering place was Reading, in the Commons.

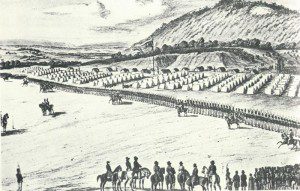

The importance of the battalion encampment of May 1842 can be judged by the fact that two separate lithographs were created to commemorate the event. Reviewing the troops on that auspicious occasion was none other than Gen. Winfield Scott, who was welcomed into town like visiting royalty. Be aware that relative distance in this view leaves much to be desired..

As journalist Benjamin A. Fryer once noted in regard to Battalion Days: “They were patriotic, colorful, exciting and social, knitting the people together in a common cause — defense of country. There were drills, inspections, uniformed men, parades, stirring music, flags, much dining and considerable drinking and dancing at all the local taverns.”

The greatest Battalion encampment in Berks took place in Reading in May 1842. Fully 2,000 uniformed men participated. For a week they camped in tents throughout Penn’s Common and as far north as Hampden (Park) Spring.

On the “big day”, May 21, 25 companies took part in a parade that went up and down Penn Street to the cheers of some 20,000 appreciative spectators.

For the record, the local militia, which did much of its drilling in the Commons, considered such use of the land its primary purpose. Since many of the community leaders were active militiamen, that notion carried a lot of weight.

| Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 |