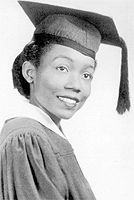

Bessie Reese Crenshaw: First Black Graduate of Kutztown University

By MARY ANN WATTS

It was 1946 and as she stood in line to register as a freshman at Kutztown University Bessie Reese Crenshaw noticed that she was the only African American in the room. Before her turn arrived, an administrator approached her and requested that she step aside. Bessie was led into small room and asked to write a paragraph, which she did, apparently satisfactorily. Bessie Reese Crenshaw was not about to let prejudice affect her ability to get an education at Kutztown State Teacher’s College (now Kutztown University).

For two years she stood out as the only African American student at the college (Tower Summer 2005). It was obvious to her that many of the students had not had experience with people of color. Some stared, some spoke, some questioned, and some ignored her. It was difficult, but Bessie’s drive and determination would not allow her to give up. Speaking of her experiences, Crenshaw said, “I had a locker next to a girl for an entire year and she refused to even to talk to me. I felt isolated at times, invisible, but I wanted to be a teacher and I got my education.” (Kutztown University Magazine, Summer 2000).

Often, she was asked by students and teachers if she might not “be more comfortable” at an all-black school. Having grown up in a multi-ethnic neighborhood in Reading, Crenshaw saw nothing different in the make-up of the students at the college. Polish, Greek, Pennsylvania German, Italian, and African American had all lived on the same street, attended the same elementary school, junior high school, and subsequently Reading High School. Why not college too? Despite the ethnic and racial diversity of her neighborhood, all Crenshaw’s teachers were white. She had no African American teachers in public schools of Reading or in college at Kutztown.

Convenience and proximity had as much to do with Crenshaw’s desire to attend Kutztown College, as did her quest for an education. Living on campus was not an option. Crenshaw was born Bessie Pritchard Reese, the second oldest child of a widowed mother. Her father died young when all of the children were under five years of age. Crenshaw’s mother chose to remain in Reading rather than return to her ancestral home in Virginia. Here, she knew that her children could get a good education and that was important to her.

Bessie’s mother held the family together financially, spiritually and emotionally. While the children were in grade school, she stayed home to take care of her young family. She “took in washing” to help support her family. When the children were old enough, she worked outside the home as a domestic to support her family.

Christmas and holidays were difficult for the family since there would be few gifts and toys. Sometimes the YWCA would see that each child got at least one toy. The family looked forward to Sunday School at Christmas time. They would perform the recitations that they had learned. Their teachers rewarded each child with the gift of an apple, orange, candy cane and nuts. The young Bessie busied herself with church and school activities. She especially enjoyed singing and became a member of both the church and school choirs.

To finance college, the bright Crenshaw received funds from a Negro organization, the J.F. Goodwin Scholarship Club. The organization gave scholarships to deserving students continuing their education post high school. The scholarship club was founded by a black doctor, who realized the need for African American students to be educated. According to Crenshaw, Dr. James F. Goodwin would take groups of African American students to visit the traditional black colleges to make them aware of the possibility of college attendance. The J.F. Goodwin Scholarship Club exists today and still helps students get an education by supplying financial aid (Tower Summer 2005).

Crenshaw credits her ability to accomplish her goals to her mother, who was a constant inspiration; her family; the support of the Negro community; the J.F. Goodwin Scholarship Club; her church, who gave financial support from time to time; and the local Black Beneficial Protective Order of Elks. It really does take a village to raise a child and the Negro village of Reading helped raise this child.

Crenshaw remembers fondly, growing up in Reading. She attended Buttonwood and Pear Elementary School, which was within one block from her home. Her third grade teacher was her favorite and her favorite subjects were Reading, Spelling, Writing, Music, Art, English and Ancient History (everything except Math).

Trips to the Reading Museum were memorable; there she studied different kinds of artwork, other cultures, and was exposed to lectures and films. She found May Day a day of rejoicing since she got new shoes to perform the dances: European polkas, schottisches, and round dances. She also got a new dress and new hair ribbons. She recalls wrapping the “May pole” as a memorable activity.

In Junior High School, as an outstanding student, Crenshaw was elected to the National Honor Society. A star athlete, she received letters at Reading High School as a member of the track team. She has many other happy memories of growing up in Reading. Her mother made yeast bread on Sundays and the smell of the bread permeated the home. The family would go to City Park on Sunday afternoons to listen to band concerts. There was Showtime at the Rajah featuring the big band sounds of Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford, Duke Ellington and others.

It was Bessie’s responsibility to take her younger brother and sister to Sunday School and the movies. Her favorite movies were musicals and cowboy films with Hopalong Cassidy, the Durango Kid, Roy Rogers, and Gene Autry. Bessie explained, “The good guys always won in the end and the bad guys went to jail, which was a reinforcement of the rules taught in our home; that actions have consequences.”

She and her siblings saw movie stars Gene Autry and Roy Rogers in person. They also saw local celebrities Uncle Jack and Mary Lou. Crenshaw also enjoyed the serials like the Drums of Fu Manchu and radio plays featuring Helen Hayes. Even though there was not an abundance of money in the family, Crenshaw’s mother was able to provide many meaningful experiences for her children.

During the summers, while Bessie was attending Kutztown University, she worked in the hospital ironing doctor’s coats on a pressing machine, at the seashore, and as a children’s nurse. She rode the bus from Reading to Kutztown and sometime got rides from other commuting students. Even with the challenges of getting to school, Crenshaw found time to participate in intramural sports, the choir, and youth leadership. She also worked for the commuting women’s league as secretary (Tower Summer 2005).

With all of the challenges that attending college presented, Crenshaw persevered and graduated in 1950 from Kutztown University. Believing that some one must have achieved that distinction earlier, Crenshaw was not aware that she was the first African American graduate until the college contacted her.

Following graduation, Crenshaw found she was well equipped and prepared to teach children, but there was no job to be had in Reading or Berks County. Reading was not ready to employ an African American teacher and would not be ready until seven years later when Velma King Bannerman was hired. A nice principal that Crenshaw had met in Atlantic City during one of her summer jobs encouraged her go south and recommended her to a principal in Method, NC which was three miles from Raleigh. She had never been south before but looked forward to a new life and meeting new people.

Crenshaw taught at the Berry O’Kelly School, which had been a former boarding school for black students whose families could afford to further their education. It was no longer used for that purpose and had been converted to an elementary and high school. Crenshaw lived in a room in the old dormitory. Living there gave her a taste of the college life and dormitory living that she had been unable to experience at Kutztown.

She felt proud to meet other teachers when they assembled. Everyone was black, the teachers, the principal, the students. She taught a combination of third and fourth grades and later a fifth grade. Crenshaw had wonderful experiences in Method. It was astonishing to see people of color working as mailmen, doctors, lawyers, dentists, barbers, pharmacists, and librarians. It was so different from Berks County!

Crenshaw also had experiences that shocked and distressed her. The students requested and paid for rental books that were old. Many of the children had potential, but could not always attend school since they had to pick cotton. Many times supplies were limited and Crenshaw used her own money to buy materials that were needed. Many times the teacher had fundraisers to raise money for supplies. She remembers making candy apples to sell and using the money for school supplies. It saddened her that children, because of segregation, were faced with so many obstacles.

When integration began in the south, Crenshaw participated in workshops with white and black teachers to help understand the needs of children of all races. She recalls that the south adapted to integration more readily than would have been supposed, and with greater acceptance than some of the schools in the north, which practiced de facto segregation. While in the South, Crenshaw received a master’s degree from North Carolina College at Durham. She is a member of the Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority.

Crenshaw returned to Reading in 1969 and by then her hometown was ready for her, an African American teacher. Illogically, the justification for not having black teachers was that white children would not relate to them. Children are honest and adaptable. There might be some wonder and curiosity if they have never had a black teacher, but they will come to love them just as they do any person who is kind and competent. Crenshaw is both. For twenty years until she retired, she taught third grade at Tenth and Green Elementary School in Reading.

The multi-talented Crenshaw is artistic and provided many opportunities for her students to participate in creative art activities. She helped plan programs for the entire school during Negro History Month, which involved art, music and literature. She was well-liked by the children and parents there.

In 2000, Kutztown University honored Crenshaw as one of the hundred graduates from 1916 to 1995, featured in KU Magazine’s commemoration of the end of the 20th Century. Chosen were alumni whose vocations or avocations represented and reflected the diversity of opportunities provided by a Kutztown education (Kutztown University Magazine Summer 2000). In her interview, Bessie made mention of the fact that she sometime felt “isolated and invisible,” but that her goal was to get an education and become a teacher: a goal that she realized.

In 2005, Kutztown University again decided to recognize Crenshaw’s distinction of being their first African American graduate. She spoke about having grown up in Reading in an ethnically diverse neighborhood and attending Reading High School, which was also ethnically diverse. She had not foreseen that attendance at Kutztown would present any problems (Tower Summer 2005).

Crenshaw gives back to the community that supported her through her membership in the “Help One Another” organization, which was founded in 1962 by Reba Templeton. The organization raises money to provide college scholarships and textbooks through the “Youth of Yesterday” program, another community organization in which Crenshaw has membership.

Crenshaw’s passions include education and helping others in their quest to get an education. She has been a tutor for the Literacy Council, a Campfire Girl leader and a volunteer at the Black Heritage Center. At the Center, a group of women sorted, compiled, and filed educational material about Black History, which could be used by schools or persons seeking information. The Center no longer exists and much of the materials have been given to the African American Museum.

For her own personal enjoyment Crenshaw takes occasional classes in art at Reading Area Community College and the Wyomissing Institute. More recently she has begun exercising at Body Zone Fitness Center.

Bessie Reese Crenshaw deserves the recognition that Kutztown University has afforded her recently. It’s ironic that honors are now afforded to a student who was not welcomed with open arms fifty-five years ago. One such honor is a seat on the Kutztown University alumni association board. In Crenshaw’s own words, “I guess I’ve come full circle.”

About the author:

Mary Ann Watts is a native of Harrisburg, Pa.,who has lived in Berks County since 1969. She is a retired elementary school teacher who has taught in Harrisburg, Baltimore, MD and Reading, PA. Sherecently enrolled in the Professional Writing Course at Penn State University and was involved in the Writing History Program, which researched information about the African American presence in Berks County. Watts has always had an interest in writing and received a second place award for an essay she wrote in high school for the American Tuberculosis Society. More recently she has receivedawards forshort stories written for contests sponsored by the Federation of Women’s Clubs. When Watts learned of Bessie Crenshaw’s distinction of being the first African American graduate of Kutztown Universityshe felt that it was worthy of being told.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2006 issue of The Historical Review of Berks County