| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 |

Time Changed Penn’s Common (City Park Annals – Part V)

From “The Passing Scene Volume 4”, Meiser and Meiser

Today’s feature – the final segment of a five-part series – attempts to trace how the large parcel of land at the head of Penn Street, set apart as early as 1749 by John and Richard Penn as public commons, evolved into the Penn’s Common that exists today.

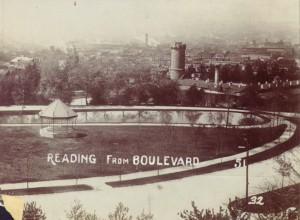

The bandstand in Penn’s Common, designed by Reading architect Alexander Forbes Smith and completed in July 1897, was 27 feet in diameter and stood 23 feet high. Notice that the roof supports resembled knights’ lances. J.S. Koch was in charge of construction.

Despite the Penns’ wishes that the common remain, in its totality, a place for “public recreation, ” the county commissioners of Berks – who had complete control of the land from 1800 to 1852 – permitted and abetted three major intrusions: the water-works, the prison grounds, and the fairgrounds.

The end result of these intrusions was that by 1854 little remained of the original commons for public use, and this small triangular plot – south of the prison -wasn’t graded and otherwise improved until 1878.

IT SHOULD BE NOTED that the act of legislature of 1852 that transferred ownership of the commons from the county commissioners to city officials had a loophole of some sort which permitted the commissioners in 1854 to lease 39 acres of prime commons land for use as fairgrounds.

While a number of influential citizens had long wanted the common – in its entirety – restored to the public, it was readily perceived that achieving such a goal would not be easy.

Indeed, there were no economically feasible means to get rid of the water-works or the prison, but the fenced-in fairgrounds was deemed a distinct possibility.

Those who wished the fairgrounds removed were cautious in their discussions as the annual fair was a great event, one which drew many to Reading – to the delight of local businessmen.

ACCORDINGLY, for a considerable period, no one seemed eager to openly start a movement to eject the agricultural society. In fact, there was doubt – even within the legal fraternity – that ejectment proceedings could be maintained.

At this juncture we turn our attention to Abner Keeley Stauffer, 1836-1906, who was born and reared in Boyertown, a son of Judge John Stauffer. After studying at Boyertown’s Mount Pleasant Seminary, which his dad helped establish in 1850, he went to Franklin and Marshall College.

After graduation from F&M in 1858 he taught a year at Boyertown and then came to Reading to read law in the office of John S. Richards.

A postcard view of Penn’s Common. The greenhouse, “Rustic Spring” and Saint Josephs Hospital are depicted.

From the time Stauffer began the practice of law in the courts of Berks, in 1861, he was a conspicuous figure in Reading. And despite the large practice that soon was his, he willingly gave his services to the public because of the deep interest he took in the advancement and welfare of his chosen community.

HE SERVED as an unpaid councilman for three terms, during which time he took the lead to rid Penn Square of its filthy and unsanitary market sheds and have declared free from toll “the three Reading (covered) Bridges” over the Schuylkill – Poplar Neck, Lancaster (Bingaman Street), and Harrisburg (Penn Street) Bridge.

While these two projects for the civic good were not accomplished without a measure of controversy, they were nothing in comparison to the “public commons issue.” For whatever reason, in 1885 Stauffer again determined to take the lead and bring the matter to a head.

In a retrospect prepared in the 1920s, Cyrus T. Fox, a newspaperman and historian who was “active on the scene” and

privy to discussions on “both sides of the fence,” penned the following regarding the fairgrounds and its ultimate removal:

“IT CAN BE STATED that the movement to transfer the property to the city for park purposes was not regarded in an unfavorable light by all members of the agricultural society. Most realized that fairs in the park had been continuing on borrowed time and that it was not a matter of ‘if’ but one of ‘when.'”

“What the society hoped for was a court decision which would forever settle the question of ownership, as the fairgrounds had, owing to the growth of the city on three sides of it, become of great financial value. There was a serious concern as to whether it was city or county property.”

“Finally, the matter got into the Berks Court of Common Pleas in the nature of an amicable action, the case being stated as the ‘Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, ex rel. city of Reading, versus commissioners of Berks County.'”

“Abner K. Stauffer appeared for the city, with George F. Baer as associate counsel.”

“The case was lost for the city in the local court but was appealed to the Supreme Court which reversed the decision and gave the (fairgrounds) land to the city. (The date of this decree was Nov. 22,1886.)

“Justice Gordon rendered the opinion that no such vague designation or use of the ground as ‘the celebrations of the agricultural society,’ specified by the (aforementioned) act of 1852, should be permitted to stand in the way of a great public necessity.

“George Baer, in his turn, brought the case before the Supreme Court. Both he and Stauffer refused to accept pay for their services. Councils (Common and Select) and the Board of Trade both passed resolutions thanking Messrs. Stauffer and Baer for their labors in behalf of the city.

“After the case in the Supreme Court had been decided, an ordinance was passed by city councils, to which Mayor James R. Kenney affixed his signature on Sept.28, 1887, setting apart ‘the tract of land situated at the head of Penn Street’ as a public common.”

IT’S WORTH EMPHASIZING that this ordinance states that the tract “shall hereafter be known and designated by the name of PENN’S COMMON.”

The Frederick Lauer Monument, unveiled in May 1885, was the first monument placed in the park. Lauer, who was the president of the United States Brewers’ Association and long involved in its activities, did more than his share to put Reading on the map.

The “Penn’s Common” designation was suggested by Baer, who felt that “City Park” was inappropriate in that there might someday be other city parks and that the Penn family should be remembered for its farsightedness in reserving this tract for the public good.

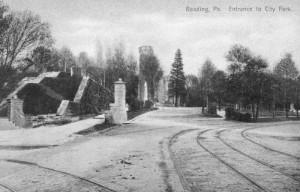

Soon after adoption of the Penn’s Common ordinance, a “park board” was formed and numerous improvements followed. These included removing all traces of the fairgrounds, laying out promenades and boulevards, and constructing ornamental retaining walls and pillars.

Designs for the “Rustic Spring” and bandstand were executed by Alexander Forbes Smith, George Baer’s favorite local architect.

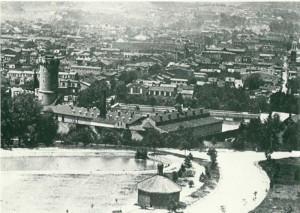

BY 1900 Penn’s Common was the most popular “place of resort” within the city proper. A Reading Eagle article of Aug. 18, 1901 reported that on a pleasant Sunday evening one might expect to encounter between 5,000 and 10,000 people “at their ease.”

It should be noted that other than the clause that permitted the Berks County Agricultural and Horticultural Society to hold its fairs in the commons -which was invalidated by decree of the Supreme Court in 1886 – all other particulars of the Act of Assembly of Feb. 17,1852 are still in force . . . or, at least, remain “on the books.”

In essence, the act states that Penn’s Common can never be used for any purpose other than as a public park and parade ground. It entirely precludes any possibility of the city ever using any portion of the land area as a site for any type of structure for governmental or municipal purposes, even for the briefest period.

This photo, taken in Penn’s Common, looks west-southwestward into Reading. Notice in the foreground the early, octagonal springhouse which also appears in an accompanying lithograph. Directly below the springhouse is “the lake”, which once had a bridge crossing it. Contrasting this view with the 1857 Geil & Shrope map makes one aware to what degree the park changed over the years. On the map the springhouse appears nowhere near any roadway.

While it is obvious city administrations of the past three decades have been oblivious of this fact, judging by the number of intrusions originating during this period, the Act of 1852 remained very much in the minds of city leaders for years following its 1886 review, modification, and reaffirmation.

A Case In Point: One of the best kept secrets of 1910 was the real reason the two reservoirs in Penn’s Common were covered over to allow for “playing on top.” Water officials feared someone would focus on the reality that in their exposed form the reservoirs occupied quite a bit of land belonging to the general public.

In the mid-1920s certain county officials, mindful that the old court house had reached the limits of usefulness, entertained the thought that an ideal site for its replacement might be the prison grounds, once the prison was removed. A gentle reminder of the terms of the Act of 1852- courtesy of the Reading Tribune – put that notion to rest.

Somewhat later, others suggested that the prison, once abandoned, might make a suitable Reading Museum. This idea was dropped when it occurred to someone that at no time could admission be charged for entrance.

THE EXISTENCE of the Act of 1852 again came to public consciousness in 1926 when city officials made plans to erect a new $750,000 City Hall – in Penn’s Common – atop the South Reservoir and skating rink.

Mary Archer and Sigmund S. Schweriner, members of the Committee for Park Preservation, filed suit on May 14, 1926 to prevent such action on the part of the city, which would have removed 3 acres and 90 perches from public access – not counting the land area that would have been taken for parking.

The bill, filed by attorneys Walter B. Freed and Cyrus G. Derr, named Mayor William E. Sharman and councilmen Fred G. Hodges, Edward C. Hunter, Jacob H. McConnell, and William J. Smith as codefendants in the action.

An aspect of the suit was to test the continuing validity of the Act of 1852.

And what was the outcome?

A strong indication might be the fact that two years later, city officials purchased the former Boys’ High School, at Eighth and Washington streets, for Reading’s new City Hall.

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 |