| Part 1 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 |

Commons Water-Works Opened In 1821 (City Park Annals – Part II)

From “The Passing Scene Volume 4”, Meiser and Meiser

In spite of the fact Penn’s Common – popularly known as city park – was intended solely as a place for “publick re-creation and resort”, county officials permitted and abetted a number of major intrusions during the years they had control of the acreage.

In the order of their occurrence, these intrusions were the water works, the Berks County Prison, and the Berks County Agricultural Association’s fairgrounds. Succeeding articles in this series will detail the latter two.

With the blessings of the county commissioners, in 1819 the state assembly empowered the Reading Water Company to sell stock subscriptions for the construction of a private water works, the accompanying reservoir of which — with its storage capacity of about 1,000 hogsheads (63,000 gallons) — would be placed near the head of Penn Street.

THE WATER itself was to come from “an inexhaustible spring” commonly called “Hampden Spring”, that then lay northeast of the town, near the present-day Spring Street.

Hampden Spring — in actuality several springs “issuing from the foot of Penn Mountain,” probably from a single source — was Reading’s only supply of tap water for nearly 20 years. Its daily discharge was rated, in 1864, at 100,000 gallons.

Originally, water from Hampden Springs traveled through hollowed-out log conduits — laid three feet below ground-level — to the reservoir in the Commons, which was 80 feet long and 34.6 feet wide.

Apparently the log conduits, installed at a cost of $3,800, proved unsatisfactory, because not long afterwards they were replaced (or partially replaced) with 2.5-inch earthen pipes at an additional expense of $2,800.

(For the record, a water report dated December 1864 gives the gravitational drop between Hampden and the Commons as 60 feet and the linear distance at about 5,000 feet.)

THE PENN’S COMMON reservoir reached completion on July 19, 1821, at which time water was allowed to flow into it. By the following October, water was being distributed to customers “down town” via log and iron conduits that varied from two to four inches in diameter.

Historian M.L. Montgomery recorded that “by 1833 the money expended in the (civic) improvement exceeded twenty thousand dollars. Then 250 families were supplied with water, and the annual income (to the works) was about $1,500. About one-fourth of the 6,500 inhabitants were supplied by the water company.”

As Reading’s population increased, so did the demand for water.

Consequently, in 1838 it became necessary to “harness” Edleman’s (Egelmann’s) Springs, situated on the opposite side of Penn Mountain just above Mineral Spring Park. This source sent some 50,000 gallons a day to the Commons, a distance of 8,892 feet, through 5-inch piping. The gravitational drop was about 90 feet.

IN ORDER to store this extra quantity of water, a second reservoir was constructed immediately north of the original one, in 1839. This new basin measured 65 by 188 feet and had a usual depth of nine feet.

In 1848, yet another reservoir was constructed immediately north of the second. Measuring an impressive129 by 248 feet, with a depth of 13 feet, this unit — which remains in use — was built to contain 2.5 million gallons of water

Incidentally, not one of our local-history books makes mention of the 1839 “middle” reservoir, yet the three basins are plainly shown and labeled on the Sidney & Clark 1849 wall map of Reading.

On December 8, 1853 the reservoir complex in the Commons, containing 3 acres and 90 perches, was deeded by the county commissioners of Berks to the Reading Water Company. They, in turn, sold it to the city on April 1,1865 for $300,000.

DURING 1872-1873, the middle and old south basin were replaced by one large south basin that, at the time of its completion, held 3,045,000 gallons.

A 1906 EAGLE ARTICLE (uncovered during the time this volume was being prepared) provides additional information of interest. What follows, in italics, is that article – with minor cuts.

The oldest residents of Reading recollect when there was only a small reservoir, built of stone, on the unenclosed commons at the head of Penn, and that there was a frame structure of rough boards over it, having one door and no windows.

Charles Breneiser, who lived with his parents on Perkiomen at the corner of Wunder, opposite the commons, 70 years and longer ago, said that when he was a boy he often played marbles with other lads around the old frame building that covered the first reservoir, and that he well recollects its appearance.

On the occasion of the celebration of the 80th birth-day anniversary of the late Mrs. Elizabeth Rapp, who lived at 420 North Ninth, in referring to old times, she said among other things: “I recollect well when there was a small reservoir at the head of Penn, and there was a low frame building over it, the door of which was locked. The water that was not needed to run through pipes down Penn was allowed to flow down South Eleventh, and my mother used to go that street between Penn and Franklin to do her washing.”

The Legislature passed an act, March 16, 1819, for the incorporation of the Reading Water Company, and John Spayd, Frederick Heller, John Addams, George deB. Keim and John Burkenbine were appointed Commissioners to obtain subscriptions of 400 shares of stock at $25 each, $2 to be paid at the time of subscribing.

The company was required to erect hydrants at different places in the borough, to be used solely for the extinguishment of

Originally, water sprayed up from the center of both reservoir through “ugly, black iron pipes.” In April 1889 these were replaced by 5-foot-high, bronze-colored zinc figures of Hebe – goddess of youth and spring and cupbearer of the gods – holding a pitcher and cup. These were removed a decade later when the reservoirs were covered. On the right is an eight-sided watchman’s shelter. The large frame structure, centermost, an office for fairground officials, was removed around 1887.

fires, and water was to be supplied for domestic and manufacturing purposes at a reason-able compensation. Any persons willfully destroying or injuring any of the works of the company or corrupting and rendering unwholesome the water, were to be fined not less than $5 nor more than $20.

The company bought a tract of three acres at Hampden Spring and laid earthen pipes, 2½ inches in calibre, about three feet below the surface of the ground to “Penn’s Common,” a distance of one mile. It was stated at the time that the Hampden Spring discharged throughout the year about 60 gallons of soft water, entirely free from earthly and saline matter, per minute. A stone building, having the shape of a sugar loaf, was erected over the spring, but nearly 50 years ago a large tree, blown over during a rain storm, fell on the apex of the cone and demolished the structure, after which a square structure of mountain stone was erected.

Water First Supplied in October 1821 Water was conducted into the reservoir, at the head of Penn, on July 19, 1821, but it was three months thereafter when the water was first supplied through iron pipes to residents along the principal streets.

At the time consumers were making attachments to the main pipes laid in the streets Messrs. Vickers and Valentine offered to furnish earthen pipes each 12 inches long, manufactured by Jesse Kersey, an enterprising mechanic, of Chester county. The laying of these earthen pipes cost 12 1/2 cents per foot, while it was stated that 30 to 50 cents afoot was the cost of laying leaden pipes. As a test three pieces of earthen pipes were cemented together and “subjected to the whole pressure of the water in the reservoir without the least injury and without showing any moisture on the surface.”

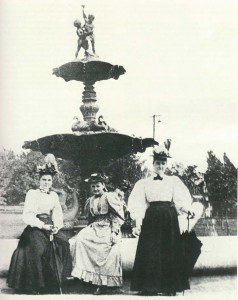

In addition to the Elk Fountain, there were three other ornamental fountains on Penn’s Common, none of which survive today. This particular view shows the one near the Walnut Street entrance – looking eastward.

Many years ago the Messrs. Eckert had a lease on a tract of land adjoining the Hampden Spring property and prospected for iron ore and found some. But it was noticed that as they dug into the side of the hill the water of the spring diminished, so to save the spring from almost total destruction the city purchased the property on which the search for iron was made. The spring is now surrounded by a tract of about 35 acres of land owned by the city.

First Officers of Water Company The stockholders of the Reading Water Company held their first meeting on the afternoon of May 8, 1820, on the second floor of the old State House, northeast corner of Fifth and Penn, to elect nine managers to conduct the affairs of the company. The following were chosen: Henry A. Muhlenberg, John Ritter, Samuel Baird, Benneville Keim, Matthias S. Richards, George Zieber, Anthony Bickel, Jacob Maurer and Daniel Fichthorn. The Board organized by the election of the following officers: President, Henry A. Muhlenberg; Secretary, Matthias S. Richards; Treasurer, George deB. Keim.

The expenses of the Water Company, from the commencement of the works up to April 1840 were $25,000, and the average net income from the water rents was $1,600 per annum. The water was then being furnished to upwards of 500 families. There were 18 fire plugs located at convenient places.

Other Water Sources Iron pipes were laid from Edelman’s spring to Penn’s Common reservoir in 1838, from Mineral Spring in 1853, from Bernhart’s Creek in 1858, from Antietam Creek in 1874, and from Maidencreek in 1889. The reservoir at the head of Buttonwood was built in 1895, but is not in service, and the water filtering plant at Dengler’s was completed last fall. (The Dengler’s plant, now abandoned, sits along Perkiomen Ave. opposite Aulenbach’s Cemetery.)

The Different Water Superintendents Thomas Kepple was the first superintendent of the water works, appointed by the old water board, and Jacob Neidert the second, who served a number of years, and he was succeeded by Marks B. Scull. Since the city owns the water works the Superintendents have been as follows: Marks B. Scull, 17 years; William B. Harper, 10 years; William B. Albright, 3 years; Emil L. Nuebling, the present incumbent, since 1895.

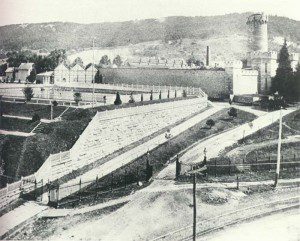

This photo, taken around 1887, shows the entrance to the Berks County Prison that stood at the head of Penn Street for 90 years. On the left we can see most of South Reservoir, which remained uncovered until 1910. Notice that there were separate, high iron fences around the prison grounds, the reservoir grounds, and the reservoirs themselves.

THOSE FAMILIAR with Penn’s Common can probably picture a vintage brick building that once served recreational purposes. This correspondent recalls playing pinochle on the second floor nearly three decades ago. Outside, men often pitched quoits during the summer months. The Reading Police Academy now occupies the premises. This structure was built in 1888 as a storage facility for the joint use of the Water, Highway, and Park departments. The water bureau paid five-eighths of its construction cost.

Before its erection, there were water-works materials all around the property. Surplus pipes used to be piled alongside the Eleventh Street fence – a high, wooden affair between Washington and Walnut streets – which afforded means of free admissions to the fair for many adventurous boys.

IN 1894, the old fencing enclosing the reservoir grounds was removed. Previously, the entrance gates were locked from sundown to sunrise. At sundown, a curfew bell was sounded to notify visitors to vacate the reservoir area. During this period, Samuel Noll was day watchman; Alfred Wartman served at night.

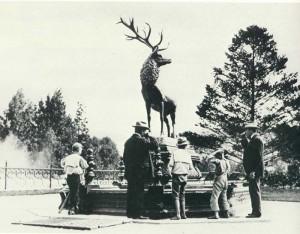

In late-April 1899, the Elk Fountain was erected. Many readers will know something about this attraction, because for years it had been the most photographed thing in the park. Postcards of it can readily be found at flea markets.

What is generally not known, though, is that this fountain was designed to dispense filtered ice water free to the public. In

The often-photographed Elk Fountain was designed and made by J.W. Fiske of New York City. The eight drinking posts surrounding the elongated octagonal basin were each 4-feet 2-inches high. The basin itself measured nearly 12 by 15 feet. Supporting the elk was a base of iron, painted black. At each end was a lion’s head which carried overflow from the filtering arrangement. The elk, described as standing in a defiant attitude, was painted in “the natural colors of the animal”.

the era when filtered ice water was a rarity even in fine restaurants, the Elk Fountain must have created quite a stir. Yet nothing of it can be found in history books, which suggests that ice water dispensing must have been a short-lived phenomenon.

WATER WAS FURNISHED to the fountain thusly: On the third floor of the aforementioned 1888 storage building was a sand filter with a daily capacity of 750 gallons, through which water passed to a 1,500-gallon storage tank.

The filtered water then flowed by gravity to a 40-gallon cooler, located in the base of the fountain in which blocks of ice were placed. Chilled water was drawn from one of six taps or faucets. Two other taps dispensed plain filtered water. Tin cups – chained fast – were provided for the convenience of the public.

As tin cups were an obvious health hazard, the faucets were soon replaced with bubble-type drinking fountains which, while sanitary, waste a good deal of water – which is probably when chilled-water dispensing came to an end.

History buff Larry W. Soltys of East Reading has a snapshot showing the once proud elk standing forlornly alongside the skating rink, minus its elaborate base and fountain setup. The view may have been taken around 1930.

DOES ANYONE know what ultimately happened to the 7-foot 6-inch zinc elk? Be apprised this was not the same elk that stood outside the Elks’ home at Fifth and Franklin streets for years.

Ice skaters on the covered-over reservoir. Notice in the background the original greenhouse and the original St. Joseph Hospital.

We conclude our brief chronology of the Penn’s Common water works of yesteryear by noting that during the winter of 1909-10 the open reservoirs were covered with cement so that the land surface could be used for public recreation.

This was done largely through the instigation of Emil L. Nuebling, once a city councilman and later chief engineer of the water bureau.

By Aug. 24,1910 roller skating atop the reservoirs was permitted. The following winter, the rink was swarming with ice skaters. Today, tennis and basketball courts occupy this area. For the record, the reservoirs below are still very much in use.

| Part 1 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 |